Volatility is the Ally of Quality, Don’t Let Anyone Tell You Otherwise

This is a piece I’ve had on the drawing board but never got around to for the better part of a month. But today someone asked me a question that inspired me to sit down and really write about it. Let’s have some eucalyptus tea…

So what does the koala actually think? After first buying Vale in 3Q20 around $10-12/share to see it run up to $23-24/sh, back to $13, back to $20+ and now back to $12-13…it is an excellent question.

Because after all, the koala is the one saying 2020 we will see an average iron ore price (62% CFR) between $100-120/t. And I continue to stand by that call, especially as we see iron ore break $100 to the downside for the first time this calendar year.

But we need to talk about a very important character trait of commodities that is in direct conflict with the 2020s version of the public markets buyside approach

There is nothing more powerful and multiple / moat accretive to an upstream commodity producer then a more volatile spot commodity price.

So let’s talk iron ore, what is the cost structure of an iron ore mine in super high level terms:

1) Mine it

2) Process it

3) Rail it

4) Load it into a boat

5) Ship it to China

So what are our big cost factors?

1) Mining and processing (strip ratio, spirals, wet/dry processiong, pelletizing, crushing, etc.)

2) Freight…(this matters if your in Brazil instead of Australia and shipping to China)

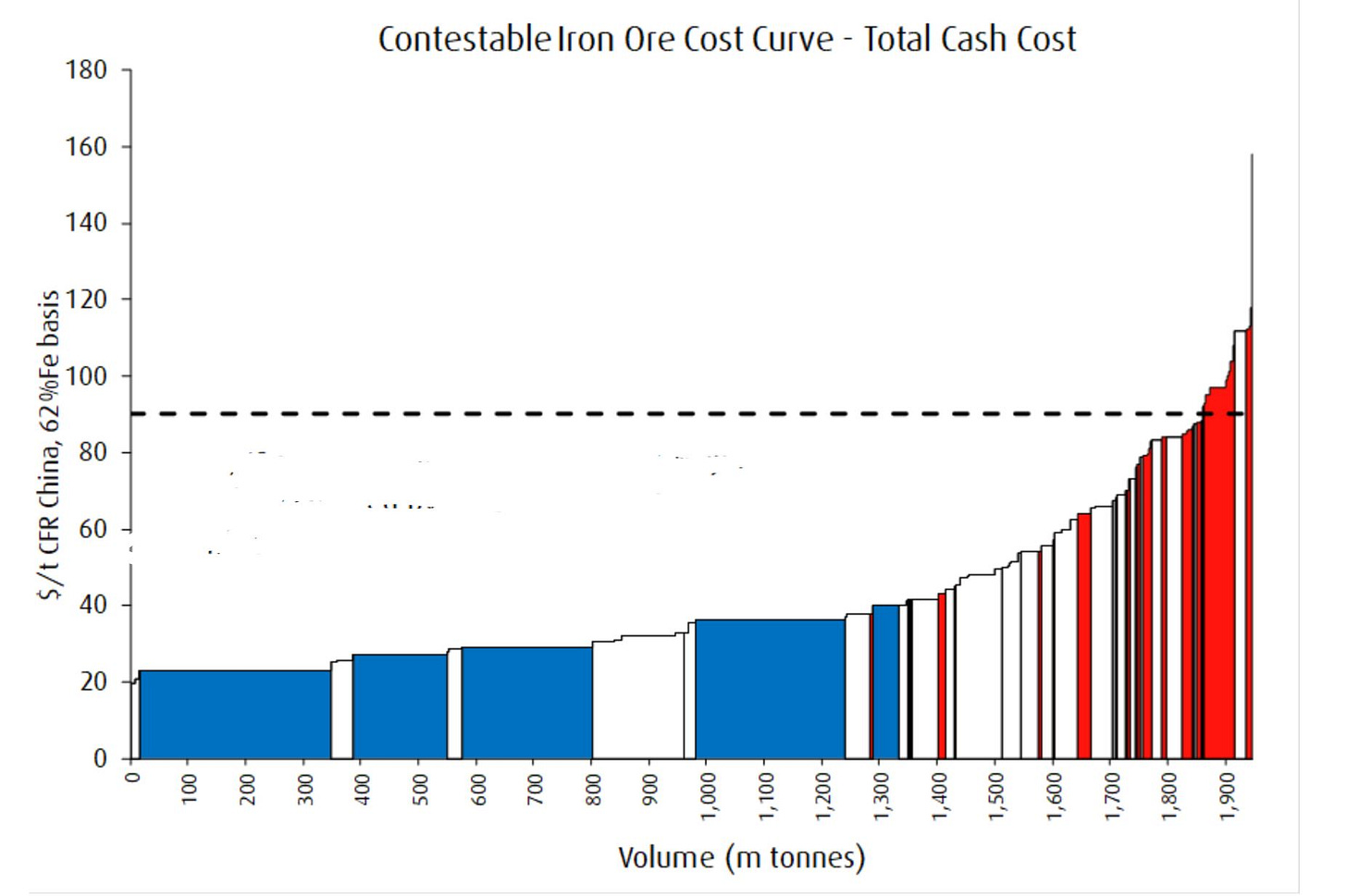

So that’s the cost model, the revenue model is sort of set by geology, but let’s just leave that to the side and just consider this. From a prominent broker, an illustrative iron ore cost curve:

Now, without seeing the legends the koala suspects you can look at that and go “I see Rio, BHP, Vale, and FMG”, and you would be right...

But what else is there?

A very steep fourth quartile.

So why is the iron ore cost curve so steep (even if we want to get detailed we could say its flat for three quartiles then hockey sticks)?

It’s because to create a world class iron ore business you need the right combination of geology (including scale of resource) and logistical excellence.

Set aside we keep being told “peak steel production” in China for the past several years, which has discouraged investment. The fact is this, world class geological endowments are world class for a reason.

What’s left outside the control of the Big 4? Simandou and Mary River?

But look again, basically the attitude in late 2015 early 2016 was “LT iron ore is $45 because that’s when the Big 4 start to lose money and it’s all over in China, it’s an ex-growth commodity”. The last 6+ years have proven that thesis incredibly incorrect but it is true that ¾ of the iron ore cost curve can be FCF positive at much lower prices. But that’s not the other quartile.

So if you ran Rio Tinto, BHP, Vale or Fortescue, what would you prefer?

1) In the 2020s iron ore is $100/t with no volatility

2) Same thing with massive volatility – think quarters of $200/t and quarters of $60/t

The answer unequivocally is the latter even though your shareholders in public markets would consider it pornographic to plug $100/t into their models for the next 8 years and see their certainty of cash flows (funny how excel gives everyone false confidence).

But the reality is this, at $100/t there are marginal project you and the koala could throw money at, get into production, get our investment paid back and a return in the 2020s. The problem though is IF the next 12 months is either $150/t or $50/t and it is a coin toss and our cost structure is $80/t, we basically need to put up not just the start up capex but cover up front losses from operations.

And this is the beautiful magic of the iron ore cost curve being a hockey stick in the fourth quartile. To compete and get into the 1-3rd quartiles requires massive capital, time, and geologic blessings.

But as long as iron ore is volatile and deranged, and people pushback on the koala’s $100-120/t call for the 2020s, the entrenched position of the Big 4 looks more powerful and harder to disrupt.

So yes, it is very unpleasant that Vale is a round trip around the world and the back besides dividends and buyback accretion, but the koala has accepted this is part of being unique in a personal investment approach.

If you sit at a multi-manager or any professional hedge fund seeking to optimize sharpe ratio and returns, the idea you want to find the most volatile commodity and invest in the highest quality producer sounds mental. Don’t you want to sleep at night?

But this is the direct conflict a Vale and say, a portfolio manager at a major fund, find themselves in. Vale should want $60/t one quarter, $140/t the next quarter, and a nice $100/t average because it prevents new entrants into the iron ore market.

But that is an institutional public equity investors nightmare.

The koala would argue however the volatility of iron ore combined with the quality of Vale’s iron ore business (or Rio Tinto, or BHP…we can talk about iron ore qualities another time around Fortescue) actually means Vale should merit a higher multiple!

The only pushback you can really give me on this is, iron ore is a shrinking market so incentives and whatever don’t matter.

In which case the koala says, sure but how has that worked out in thermal coal for you so far? And have you adjusted for low grade iron units falling out of the supply stack? Or looked at global steel consumption/production v GDP over any real time horizon?

But anyways, want to keep this simple for now.

Bottom line – if you are a high quality / high margin commodity producer, you obviously want a high average spot price over time, but you actually benefit from the volatility of that spot price being higher instead of lower. Even if it drives your shareholders crazy.

So how does the koala think about Vale trading at a ~$60Bn market cap?

It’s just a part of the investment, and the volatility makes Vale’s longer term position only stronger.

You have to learn to love volatility and chaos if you are going to invest in commodities and commodity producers such that you make it work to your longer term advantage.

Swap Vale with Alphamin and Iron Ore with Tin, and you got next week's post today! Thanks for sharing Koala.

A Tour de France analogy: As the best rider, you don't just want to finish first, you want to finish alone, that means you need to choke off your competitors, often done by varying the power zones (google it, much like your cost curve, but with heart rates) ;)

Volatility is the price we pay for outsized gains.